Experimental Nonlinear and Incremental Control Stabilization of a Tail-Sitter UAV with Hardware-in-t

Experimental Nonlinear and Incremental Control Stabilization of a Tail-Sitter UAV with Hardware-in-the-Loop Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

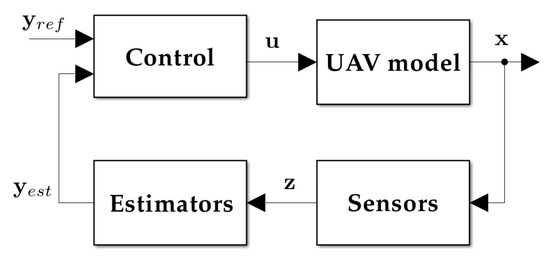

2. Aircraft Simulator

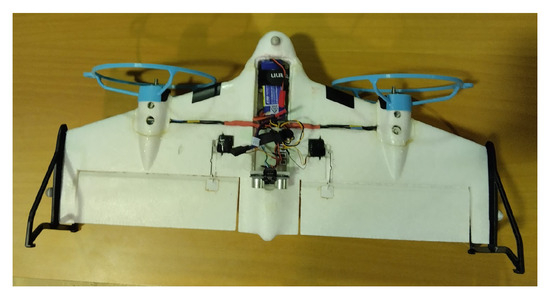

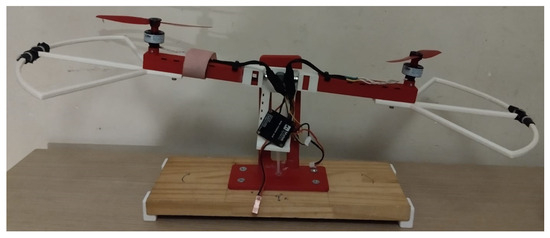

2.1. Tail-Sitter Prototype and Nonlinear Model

2.1.1. Equations of Motion

This UAV requires four inputs, namely, the deflections of the two elevons, and , and the throttle signals for the two proprotors, and , with the subscripts “R” and “L” denoting the right and left sides of the wing, respectively. However, it is more convenient to represent these inputs as the more traditional ones in flight control: and , respectively, standing for differential and simultaneous elevon deflection, representing the functions of ailerons and the elevator, and and , being the analogous inputs applied to the proprotors, taking the role of the rudder and throttle. Therefore, the input vector can be obtained from the original four inputs by applying an adequate transformation [31] and is represented by

The dynamics and kinematics of the UAV are expressed by

where represents the mass of the X-Vert, and is its inertia matrix, while and , respectively, stand for the resulting force and moment vectors acting on it. Additionally, and denote auxiliary matrices that depict the influence of and , respectively, on and , having been obtained from Ref. [31].

Four different aspects contribute to the forces and moments acting on the UAV, these being the propulsion system, the aerodynamics, the ground contact effects and the gravity. Since it is assumed that the force and moment balances are expressed in the center of gravity (CG) of the aircraft, the moment that results from gravity effects is neglected, and therefore, and are expressed by

with each of the components being described in the following sections.

2.1.2. Propulsion Forces and Moments

The rotation of each proprotor of the X-Vert generates thrust T and torque Q, which influence the propulsion force and moment , accounting for the positions of the right and left proprotors [29]:

The thrust and torque of each proprotor depend on its angular velocity and incoming airspeed. By taking as the vectorial norm of and defining as the angle that this vector makes with the rotational axis of each proprotor, the advance ratio J is obtainable, which can then be used to compute the thrust and power coefficients required for T and Q [29]:

The relationship between the angular velocity of the motors and the throttle input is modeled as the dynamics of a Brushless Direct Current (BLDC) electric motor regulated by an Electronic Speed Controller (ESC) [35], but a simplification is made by assuming the steady-state solution for the dynamics of the electric current, resulting in the first-order model

which assumes a constant battery voltage , with the torque constant, ; the back-electromotive force, ; the motor resistance, ; the rotational inertia of the proprotor, ; and the damping constant, . The values for these constants were obtained from a similar motor to the one that is used in the X-Vert, and it can be verified that the steady-state solution of (12) agrees with the motor model in Ref. [29] for the aforementioned value of .

Lastly, the rotation of the proprotors originates an induced airspeed that is dependent on the generated thrust and inflow airspeed, which can be found by solving [36]

2.1.3. Aerodynamic Forces and Moments

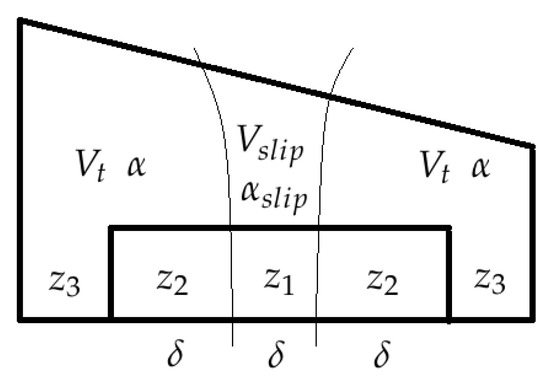

The wing of the X-Vert is modeled as a set of flat-plate segments for the left and right sides, following a similar approach to those taken in Refs. [29,37,38] but including additional aerodynamic derivatives to account for lateral aerodynamics and the effects of the angular rates [31]:

Accounting for such division, the drag D, lift L and pitching moment m for each zone can be expressed in the body frame as

where introduces the influence of the angle of attack and the sideslip angle, and , and takes on an analogous role but for the angles for zone 1, and , which account for the slipstream effects. The distance of the aerodynamic center (AC) of the right and left sides of the wing are denoted, respectively, by and , which are assumed to be the same for each side of the wing, regardless of the zone.

The drag, lift and pitching moment for each zone are obtained by using the data for the aerodynamic coefficients—, and —from Ref. [29] for the angle of attack and elevon deflection and combining them with the airspeed at each zone and its span. For example, zone 1 has a span of , which is influenced by the slipstream air velocity , and the aerodynamic coefficients account for the slipstream AOA and elevon deflection , resulting in

where denotes the mean aerodynamic chord (MAC) of the wing, and denotes the air density, both assumed to be constant. Zones 2 and 3 use for the airspeed value and as the angle of attack to obtain the aerodynamic coefficients, but zone 2 accounts for the elevon deflection, while zone 3 does not. The spans for each zone to be used in computations analogous to (21) are defined directly from the wingspan of the X-Vert, , and elevon span, : , .

The last aspect of (17) to describe is the influence of lateral aerodynamics and aerodynamic derivatives by means of and , given by

which have been adopted from Ref. [31] but modified to allow for larger values of .

2.1.4. Ground Contact Forces and Moments

The interaction of the ground is from Ref. [29], which employs a spring–damper analogy to represent the ground contact force at each contact point k, expressed in the inertial frame:

where stands for the depth of point k, and is its velocity expressed in the inertial frame, with being the position of the point in relation to the CG, where “c” denotes contact and are gains for the spring–damper system, and their values were kept the same as in Ref. [29]. also accounts for an upper limit of zero, representing the loss of contact with the ground for each point.

Five contact points were used, corresponding to the four corners of the main wing and the noise of the UAV, as shown in Appendix A, and thus, the ground force and moment vectors can be computed by expressing for each in the body frame:

2.1.5. Gravity Force

The last force acting on the simulated model of the X-Vert is gravity. As explained before, it is assumed that this force acts on the CG of the UAV, producing no moment, and therefore, its effects can be modeled by

where m/s2 denotes the gravity acceleration vector expressed in the fixed frame.

2.2. Sensors

The models for the accelerometer and gyroscope [40] are provided, respectively, by

where denotes the bias of the respective sensor, and is its zero-mean Gaussian noise vector.

The sonar sensor is mounted on the underside of the X-Vert and points to its tail, parallel to the x-axis of the body frame, and its model is given by

where represents the measurements of the sensor, is the Down coordinate expressed in the NED frame, depicts the orientation vector of the sonar expressed in this same frame, and represent the respective unit vectors, and denotes the noise of the sensor.

2.3. Attitude and Vertical Velocity Estimators

For the purpose of the stabilization of the X-Vert, the variables related to the attitude, and , are required. Additionally, the longitudinal component of the velocity, , and the Down position, , are necessary for altitude control in vertical flight. Therefore, the estimated output vector is defined as

In order to save computational resources, a choice was made to use simple and fast methods to estimate these states of complementary nature. Starting with the attitude, an estimate of is obtainable through the combination of accelerometer and gyroscope data using the Madgwick algorithm [41]:

where is an objective function to be minimized, and is its Jacobian matrix, the expressions of both having been omitted in this work but being readily available in the original research [41]. This estimator includes the accelerometer readings in and combines them with the integration of the gyroscope measurements , balancing the relative weights between both with the scalar , which takes the role of the single design variable for adjusting this estimator. Since the accelerometer does not perceive any change in rotation over an axis aligned with the gravity vector, the estimator is subject to some drift, as it relies only on the gyroscope integration for these cases. Nonetheless, for short flight times, it provided satisfactory results, presenting a fast and simple estimation strategy for the attitude in vertical flight while acting as a filter for the noise present in the sensors.

Following analogous reasoning, the readings from the accelerometer, excluding the gravity contribution, can be integrated to estimate the velocity over the x-axis of the UAV, while another estimate of it is obtainable by deriving sonar readings. By pairing both of these in the form of a more conventional complementary filter [31], the longitudinal velocity can be computed by filtering and combining both of these estimates according to

in which is a design variable, and where and are the previously described estimates of from the sonar and accelerometer, respectively, defined by

and and denote, respectively, the low-pass filter and high-pass filter, both first-order as defined in Ref. [31]. Despite being a somewhat rudimentary estimation method when compared to more complex sensor-fusion algorithms like the Kalman filter [31], the combination of these two estimators provides observations of all the necessary variables at a relatively low computational cost, with the added benefit of requiring only two design variables — and .

3. Nonlinear Control Strategies for Tail-Sitter UAV Vertical Flight

3.1. Equilibrium at Hover

Under the assumption that no wind is present, the equilibrium conditions for the X-Vert in hovering flight can be evaluated by computing the steady-state solutions of (3) at a given nonzero altitude and knowing that , m/s. Under such conditions, the thrust generated by both motors must be equal to the opposing forces, namely, the gravity and aerodynamic drag resulting from a nonzero slipstream velocity behind the propellers, and the ground contact force will be zero. Thus, the value for can be obtained by numerically solving the equation

Once has been determined, the necessary throttle to maintain a hovering condition, , can be found by computing the steady-state solution of (12). By performing these two steps, the values of rad/s and were determined using the parameters of the X-Vert in Appendix A. Therefore, the state and input vectors when hovering become

in the corresponding units.

3.2. Rotational Dynamics in Affine Form

The NDI control strategy requires that the system to be controlled is expressed in affine form. Addressing the rotational subsystem of (3), it can be reorganized into

which, in turn, requires that the resultant moment be divided into its wing and actuator contributions, as the following equations suggest [42]:

Since depends solely on the propulsion and aerodynamics of the X-Vert, each of these must be mathematically manipulated in order to allow for the implementation of (41). Starting with (7) and linearizing it for the operating condition defined by , the moment contribution from the propulsion subsystem becomes

where and were used to simplify the notation. The second equality of (44) is achieved by performing the approximation .

A similar process must be applied for the aerodynamic contribution expressed by (17). Since , the lift, drag and pitching moment will only be influenced by the slipstream velocity on the control surfaces, and and as will be aligned with the axes of the propellers. Using a linear approximation of the aerodynamic coefficients defined by with , the aerodynamic contribution to can be approximated as follows:

It is evident from (44) and (45) that , and therefore, the and components of (41) can be adequately determined by merging (44) and (45) into

Accounting for the aforementioned assumptions, the matrix in (46) is constant and thus can be determined with the parameters and constants of the X-Vert model supplied in Appendix A. Furthermore, this matrix can be simplified considering only its diagonal, assuming that each of the components of predominantly affects , and , respectively. Therefore, its numerical value is

in appropriate units, as it will be used in the NDI and INDI controllers.

3.3. Velocity Control

In order to draw an objective comparison among the different stabilization methods for the X-Vert, a suitable forward velocity controller must be chosen, and care must be taken that it ensures a minimal slipstream velocity to provide control authority to the elevons. As the design of such a controller falls out of the scope of this work, and the strategy of Ref. [29], taken as the benchmark nonlinear controller, already provides an adequate solution, this was adopted. It consists of determining the desired thrust that tracks the references for and ,

in which and .

Knowing the desired forward force, the propeller model (9) can be used to determine the angular velocity and motor torque, which, in turn, allow the throttle input to be computed. Nonetheless, as explained in Ref. [29], it is useful to provide a lower boundary on to ensure a minimum slipstream airspeed of 7 m/s on the control surfaces, and an upper limit so it can have some yawing authority:

3.4. Attitude Stabilization

3.4.1. Benchmark Nonlinear Controller (BNC)

The controller used as a benchmark for attitude stabilization is an adaptation of the one in Ref. [29], made by applying the previously referred assumption of zero airspeed, . Similarly to the velocity controller, a desired set of moments can be defined by

where and are 3-by-3 diagonal gain matrices, with elements for , and stands for the vectorial components of —the error quaternion—which results from the quaternion product of the conjugate of with [29,32]. Knowing and obtaining from (49), the required thrust for each motor is computed from

From and , the angular velocity of each motor can be computed by inverting the propeller model in (9). In turn, knowing and enables the calculation of and by solving (12) under steady-state conditions. Lastly, the elevon deflections are obtained from

where and represent, respectively, the rolling and pitching moment deflection coefficients in the slipstream, as defined in the original research work [29].

It is useful to reorganize the inputs that result from the BNC in an expression analogous to (1), allowing them to be compared with their respective counterparts that result from the remaining controllers:

3.4.2. Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion (NDI) Controller

The application of NDI to the attitude stabilization problem consists of the inversion of the model of the system so that the resulting inputs enable the aircraft to follow the desired dynamics, which can be made to depend on the relevant error variables:

3.4.3. Incremental Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion (INDI) Controller

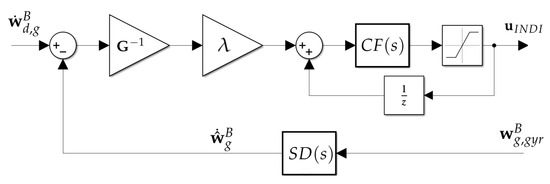

The third attitude controller is the incremental version of NDI, INDI. Generically, the INDI control is deduced from (41) under the assumptions that the control inputs have a higher impact on the dynamics of the aircraft and a high sample rate is possible [13]. An increment for the control action can then be computed, accounting for the control-effectiveness matrix to allow for the tracking of , as defined by (55) [17]:

where an additional scaling factor is included, acting as a low-pass filter in the computation of [13,43]. Nonetheless, Equation (57) assumes that the angular acceleration is available, and therefore, it must be estimated. A second-order derivative filter is used, as it is based on a method of estimating from the gyroscope readings [44], illustrated by

Assuming the damping coefficient , the trade-off value for the cutoff frequency must be found when tuning the INDI controller, aiming to find a balance between an acceptable level of noise and the delay introduced by the filtering operations [43]. An additional tool that helps in achieving a control action robust to noise is a command filter:

which acts as a low-pass filter and saturation to enforce the limits of the actuators, defined by a single parameter, [44].

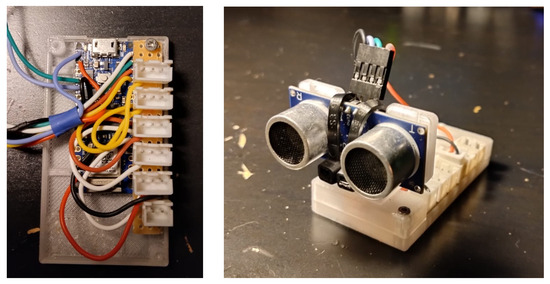

4. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation

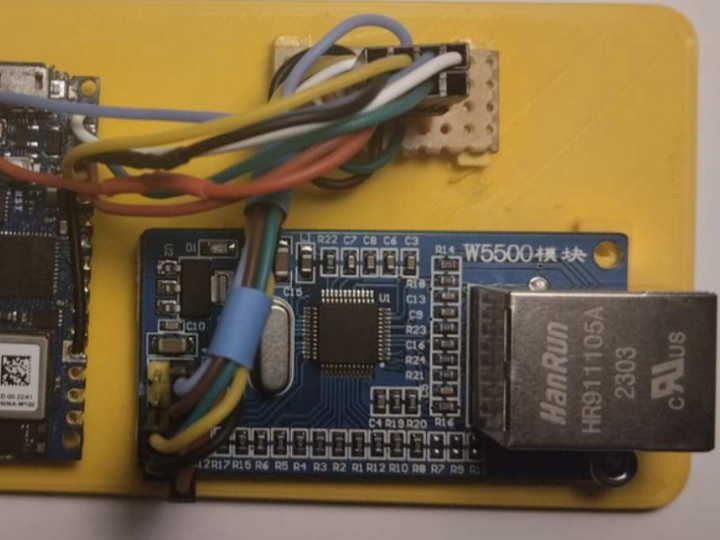

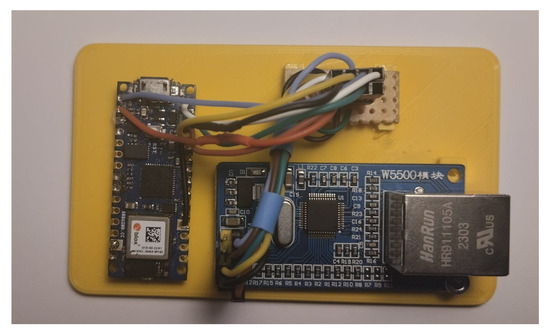

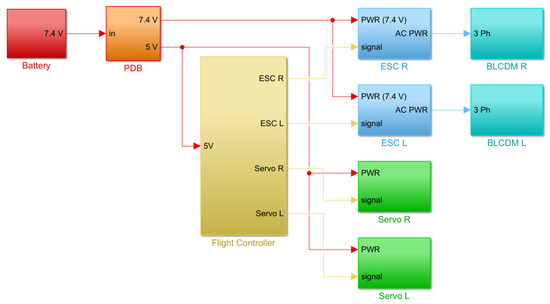

4.1. Hardware and Communications

4.2. Benchmark Maneuver for Vertical Flight

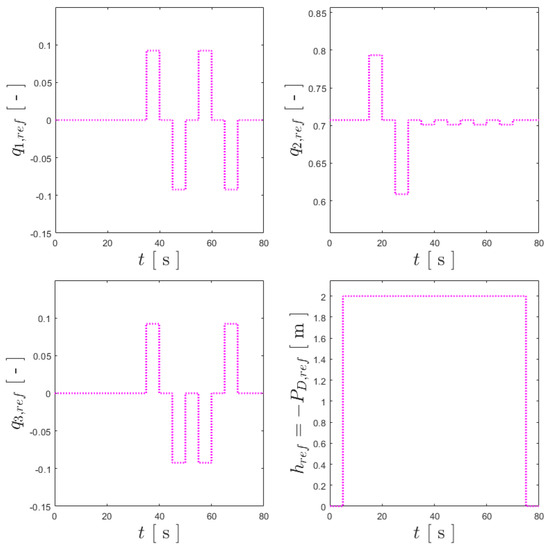

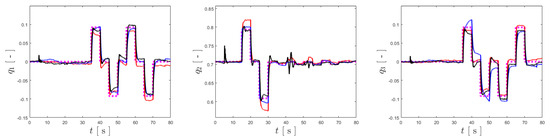

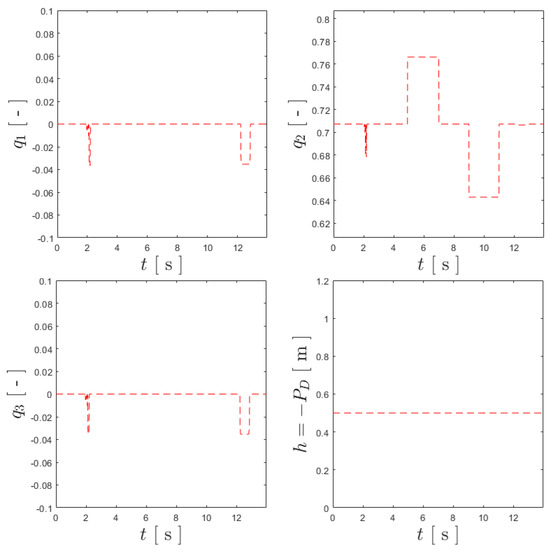

To validate the different attitude control solutions, a set of maneuvers had to be designed, allowing the degrees of freedom of the stabilized UAV to be explored. As depicted in Figure 6, these maneuvers correspond to a time-varying vector of references:

which enables forward velocity, angular velocity, altitude and attitude values to be tracked by the controllers, where was taken as zero for attitude stabilization.

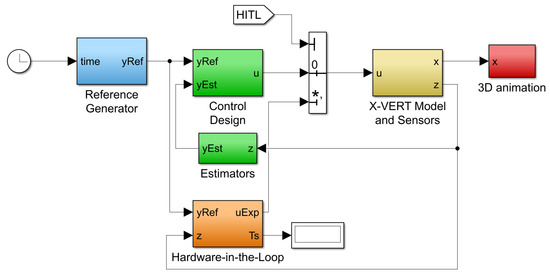

4.3. Simulation Environment

Filter discretization: While MATLAB allows the implementation of transfer functions in continuous time, a discrete form is desired to validate the MCU implementation of the HPF and LPF for the velocity estimation in (35) and the SD and CF filters—respectively, (58) and (59)—for the INDI controller. The bilinear transformation

is employed for this purpose, and the deduction of the discrete expressions for each of the previously referenced filters is omitted.

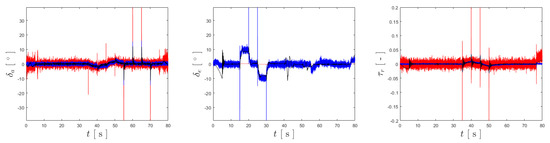

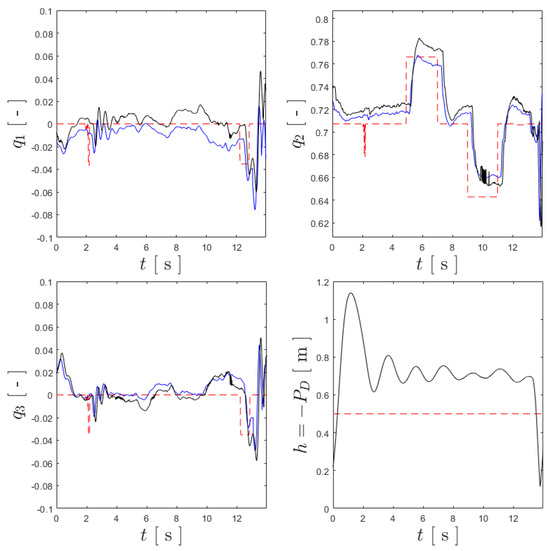

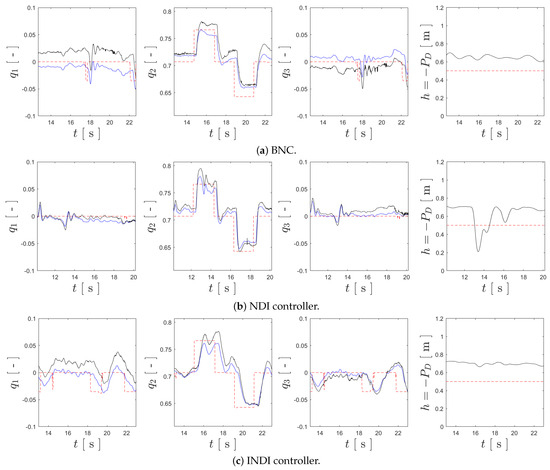

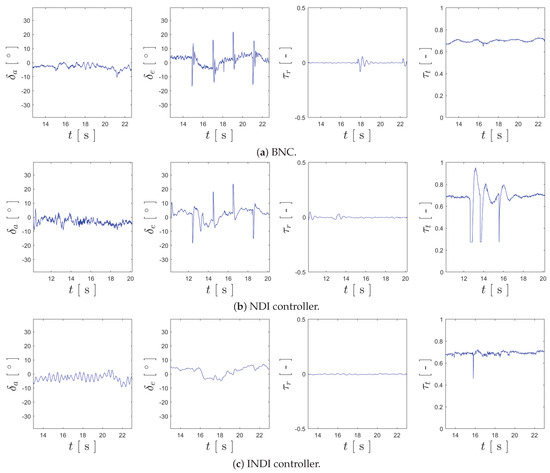

4.4. Simulation and HITL Results

Regarding the metrics to evaluate in order to be able to draw an objective comparison among the different control solutions for the X-Vert, two were chosen. The first was the root-mean-square error, , of the three vectorial components of the quaternion, , and , when compared to the respective references,

to analyze the tracking performance. The second was the oscillation of the actuators, represented by and obtained by computing the RMS of the control action with that obtained after applying a tenth-order median filter, the aim of which is to attest to the smoothness of the control action of each controller and, therefore, its robustness to sensor noise:

4.4.1. Simulation Results

4.4.2. Hardware-in-the-Loop Results

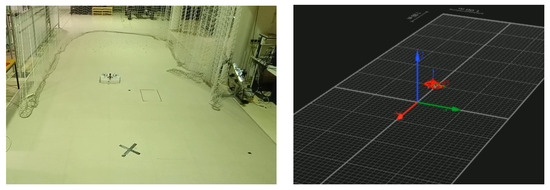

5. Experimental Validation

5.1. Flight Controller Design

5.2. Ground Truth

5.3. Benchmark Maneuver for Experimental Vertical Flight

5.4. Parameter Tuning for Experimental Flight

The adaptation to an experimental scenario necessitated another parameter tuning in order to accommodate such changes. It was soon realized that the Arduino Nano 33 IOT could not perform the cycles at 200 Hz when using UDP over Wi-Fi, and thus, a sample time s was used instead, as it proved to be sufficiently low to stabilize the aircraft. The estimators and controllers were subject to a re-tuning as well, imposed not only by the transition from the simulation to the experimental setting but also by the change in the sampling frequency. Similarly to the simulation and HITL results, an effort was made to ensure that the parameters of the estimators and altitude controller were the same for the trials using different attitude controllers, and their values are

5.5. Vertical Flight Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC | Aerodynamic center |

| AOA | Angle of attack |

| BLDC | Brushless Direct Current |

| BNC | Benchmark nonlinear controller |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CF | Complementary/Command Filter |

| CG | Center of gravity |

| DOF | Degree of freedom |

| ESC | Electronic Speed Controller |

| FC | Flight controller |

| HITL | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| HPF | High-pass filter |

| I2C | Inter-Integrated Circuit |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| INDI | Incremental Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion |

| LPF | Low-pass filter |

| LQR | Linear Quadratic Regulator |

| MAC | Mean aerodynamic chord |

| MCS | Motion capture system |

| MCU | Microcontroller unit |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NDI | Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion |

| NED | North–East–Down |

| PCB | Printed circuit board |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| PWM | Pulse-width modulation |

| QTM | Qualysis Track Manager |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| SD | Second-(order) derivative |

| SPI | Serial Peripheral Interface |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| VTOL | Vertical Take-off and Landing |

Appendix A. X-Vert Simulator Parameters and Constants

Appendix A.1. General Parameters

Appendix A.2. Propulsion Subsystem

Appendix A.3. Aerodynamic Subsystem

Appendix A.4. Ground Contact Subsystem

Appendix A.5. Sensors

References

- Telli, K.; Kraa, O.; Himeur, Y.; Ouamane, A.; Boumehraz, M.; Atalla, S.; Mansoor, W. A comprehensive review of recent research trends on unmanned aerial vehicles (uavs). Systems 2023, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Han, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Li, J. A Survey on UAV Applications in Smart City Management: Challenges, Advances, and Opportunities. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 8982–9010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehreh, B.; Moutinho, A.; Viegas, C. Latest Trends on Tree Classification and Segmentation Using UAV Data—A Review of Agroforestry Applications. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh, D.; Kumar, N.A.; Sivaguru, M.; Keerthivaasan, K.V.R.; Janaki, B.R.; Raffik, R. Role of UAVs in innovating agriculture with future applications: A review. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advancements in Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computing and Automation (ICAECA), Coimbatore, India, 8–9 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, A.S.; Younes, A.B.; Cai, C.; Cai, G. A survey of hybrid unmanned aerial vehicles. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 98, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducard, G.J.; Allenspach, M. Review of designs and flight control techniques of hybrid and convertible VTOL UAVs. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 107035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; Jayachdran, S.; Kenche, S.; Katoch, A.; Suresh, A.; Gundabattini, E.; Selvaraj, S.K.; Legesse, A.A. A Review on Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) Tilt-Rotor and Tilt Wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). J. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1803638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, M.; Shah, J.; Fauzi, W.; Hanouf, Z. Gain scheduled linear quadratic control for quadcopter. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 270, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poksawat, P.; Wang, L.; Mohamed, A. Gain scheduled attitude control of fixed-wing UAV with automatic controller tuning. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2017, 26, 1192–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Gain scheduling based PID control approaches for path tracking and fault tolerant control of a quad-rotor UAV. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Robot. Res. 2018, 7, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.G.; Andrade, F.A.; Guedes, I.P.; Carvalho, G.F.; Zachi, A.R.; Pinto, M.F. Fuzzy gain-scheduling PID for UAV position and altitude controllers. Sensors 2022, 22, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashilkar, A.A.; Ismail, S.; Ayyagari, R.; Sundararajan, N. Design of a nonlinear dynamic inversion controller for trajectory following and maneuvering for fixed wing aircraft. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications (CISDA), Singapore, 16–19 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Azinheira, J.R.; Moutinho, A. Hover Control of an UAV with Backstepping Design Including Input Saturations. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2014, 16, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.F. Non-linear dynamic inversion control design for rotorcraft. Aerospace 2019, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, P.; Deng, H.; Chen, B. Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion Control of VTOL Tilt-Wing UAV. In Proceedings of the 2018 Eighth International Conference on Instrumentation & Measurement, Computer, Communication and Control (IMCCC), Harbin, China, 19–21 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Z. A Backstepping Control Strategy for Fixed Wing UAV under Actuator Failure. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smeur, E.J.; Chu, Q.; De Croon, G.C. Adaptive incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion for attitude control of micro air vehicles. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2016, 39, 450–461. [Google Scholar]

- Azinheira, J.R.; Moutinho, A.; Carvalho, J.R. Lateral control of airship with uncertain dynamics using incremental nonlinear dynamics inversion. IFAC Pap. Online 2015, 48, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieberling, S.; Chu, Q.P.; Mulder, J.A. Robust flight control using incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion and angular acceleration prediction. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2019, 33, 1732–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquatella, P.; van Kampen, E.; Chu, Q.P. Incremental backstepping for robust nonlinear flight control. In Proceedings of the EuroGNC 2013, Delft, The Netherlands, 10–12 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, N.M.; Moutinho, A. Robust incremental backstepping controller for the attitude and airspeed tracking of a commercial airplane. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th International Conference on Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (ICMAE), Brussels, Belgium, 22–25 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, R.A.; Azinheira, J.R.; Moutinho, A. Robustness of incremental backstepping flight controllers: The boeing 747 case study. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 3492–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, E.; Karaman, S. Accurate tracking of aggressive quadrotor trajectories using incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion and differential flatness. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2020, 29, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, B.; Giri, D.K.; Ghosh, A.K. Attitude Tracking Control of a Light Aircraft Using Classical and Incremental Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 15–18 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Smeur, E.J.; Bronz, M.; de Croon, G.C. Incremental control and guidance of hybrid aircraft applied to a tailsitter unmanned air vehicle. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2020, 43, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, E.A.; Karaman, S. Global trajectory-tracking control for a tailsitter flying wing in agile uncoordinated flight. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2021 Forum, Online, 2–6 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, E.; Karaman, S. Global incremental flight control for agile maneuvering of a tailsitter flying wing. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2022, 45, 2332–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yang, J. INDI-based transitional flight control and stability analysis of a tail-sitter UAV. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 11–14 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappinelli, R.; Nahon, M. Modeling and Control of a Tailsitter UAV. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dallas, TX, USA, 12–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- E-Flite XVERT VTOL Webpage. Available online: https://www.horizonhobby.de/en_DE/product/x-vert-vtol-bnf-basic-504mm/EFL1850.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Beard, R.W.; McLain, T.W. Small Unmanned Aircraft: Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, B.L.; Lewis, F.L. Aircraft Control and Simulation: Dynamics, Controls Design, and Autonomous Systems, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.C. Flight Stability and Automatic Control, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Whidborne, J.; Mendez, A.; Cooke, A. Effect of Rotor Tilt on the Gust Rejection Properties of Multirotor Aircraft. Drones 2022, 6, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Nahon, M. Toward an accurate physics-based UAV thruster model. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2013, 18, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, B.W. Aerodynamics, Aeronautics and Flight Mechanics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, W.; Nahon, M. Real-time modeling of agile fixed-wing UAV aerodynamics. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Denver, CO, USA, 9–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, W.; Nahon, M. Modeling dynamics of agile fixed-wing UAVs for real-time applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 7–10 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prisacariu, V.; Cîrciu, I.; Boscoianu, M. Flying wing aerodynamic analysis. Rev. Air Force Acad. 2012, 2, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, D.J.; Moutinho, A.; Azinheira, J.R. Stabilization and altitude control of an indoor low-cost quadrotor: Design and experimental results. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions, Vila Real, Portugal, 8–10 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Madgwick, S.O.; Harrison, A.J.; Vaidyanathan, R. Estimation of IMU and MARG orientation using a gradient descent algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, Zurich, Switzerland, 29 June–1 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Acquatella, P.; van Ekeren, W.; Chu, Q.P. Pi (d) tuning for flight control systems via incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion. IFAC Pap. Online 2017, 50, 8175–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, R.A.; Azinheira, J.R.; Moutinho, A. Cascaded incremental backstepping controller for the attitude tracking of fixed-wing aircraft. In Proceedings of the 5th CEAS Conference on Guidance, Navigation and Control, Berlin, Germany, 3–5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, R.A.; Marton, A.S.; Azinheira, J.R.; Carvalho, J.R.; Moutinho, A. Increased robustness to delay in incremental controllers using input scaling gain. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 58, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduino Nano 33 IOT Product Page. Available online: https://docs.arduino.cc/hardware/nano-33-iot/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Wiznet W5500 Product Page. Available online: https://www.wiznet.io/product-item/w5500/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- CAD Model UAV Tailsitter at GrabCAD Website. Available online: https://grabcad.com/library/uav-tailsitter-1 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Spektrum A220 4g Aircraft Servo Product Page, Horizon Hobby Website. Available online: https://www.horizonhobby.com/product/a220-4g-aircraft-servo-x-vert/SPMSA220.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- 20A Nano ESC Product Page, SkyRC Website. Available online: https://www.skyrc.com/Discontinued_Products/20A_ESC (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- BL280 Brushless Outrunner Motor 2600Kv Product Page, Horizon Hobby Website. Available online: https://www.horizonhobby.com/product/bl280-brushless-outrunner-motor-2600kv/EFLM1809.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Mini Power Hub Product Page, MatekSys Website. Available online: http://www.mateksys.com/?portfolio=hub5v12v#tab-id-1 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Gens Ace G-Tech Soaring 450 mAh 7.4 V Battery Product Page, Gens Ace Website. Available online: https://www.gensace.de/gens-ace-g-tech-soaring-450mah-7-4v-30c-2s1p-lipo-battery-pack-with-jst-syp-plug.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Qualysis Track Manager Software, Qualysis Website. Available online: https://www.qualisys.com/software/qualisys-track-manager/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).